The Tecumseh

Technical Data

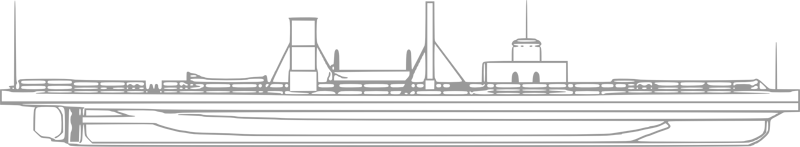

Canonicus-class monitor

Displacement: 1,034 ton.

Length: 223 ft. Beam: 44 ft 4 in. Draft: 13 ft 6 in.

Propulsion: Ericsson Vibrating Lever Steam Engine, 2 Stimers fire-tube boilers, 320HP, 1 shaft, 8 knots

Complement: Reports range from 84 officers and enlisted to 120. Sailed with a known verified complement of 110 during the Battle of Mobile Bay.

Armament: 2 × 15-inch smoothbore Dahlgren guns

Armor: Gun turret: 10 in, Waterline belt: 5 in, Deck: 1.5 in, Pilot house: 10 in

Contract for the Tecumseh was awarded to Charles Secor & Company 15 September 1862.

Constructed at Joseph Coldwell, Jersey City, NJ with Chief Engineer John Faron, USN, assigned as construction inspector.

Launched 12 September 1863 with Kate Gregory, daughter-in-law of RADM Francis Gregory, as sponsor.

Commissioned 19 April 1864 with CDR Tunis A. Craven commanding.

Service History

(via Wikipedia entry for U.S.S. Tecumseh)

After commissioning, the Tecumseh was ordered to join the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron at Newport News and arrived there on 28 April. Tecumseh was ordered to protect the transports conveying Major General Benjamin Butler's Army of the James up the James River at the beginning of the Bermuda Hundred Campaign on 4 May. To prevent Confederate warships from coming down from the James, the Union forces blocked the channel in mid-June 1864. Tecumseh sank four hulks and a schooner and laid several boom across the river as part of this effort. On 21 June, Commander Craven spotted a line of breastworks that the enemy was building at Howlett's Farm and the ship opened fire at the workers. The Confederates replied with a battery of four guns near the breastworks and her sisters Canonicus and Saugus joined in the bombardment. A half-hour later, Confederate ships near Dutch Gap joined in, but their fire was ineffective because they were firing blindly at the Union monitors. During the engagement, Tecumseh fired forty-six 15-inch shells and was not hit by any Confederate shells. Craven claimed the destruction of one gun emplacement.

Two days after the battle, Tecumseh sailed down the James for Norfolk, but ran aground en route when her wire steering ropes broke after having been burned half way through by the heat of her boilers. She was refloated four hours later and spend a week in Norfolk making repairs and taking on supplies. On 5 July, the ship got underway for Pensacola, Florida to join the West Gulf Blockading Squadron, towed by the side-wheel gunboats Augusta and Eutaw. The ship's engine had overheated en route and required a week's repairs at Port Royal, South Carolina and Augusta had to turn back with engine problems, but Eutaw and Tecumseh arrived in Pensacola on 28 July. Towed by the side-wheel gunboat Bienville, the monitor arrived off Mobile Bay on the evening of 4 August.

Farragut briefed Craven on his ship's intended role in the battle. She and her sister Manhattan were to keep the ironclad ram CSS Tennessee away from the vulnerable wooden ships while they were passing Fort Morgan and then sink her. The river monitors Winnebago and Chickasaw were to engage the fort until all of the wooden ships had passed. The four monitors would form the starboard column of ships, closest to Fort Morgan, with Tecumseh in the lead, while the wooden ships formed a separate column to port. The eastern side of the channel closest to Fort Morgan was free of obstacles, but "torpedoes" were known to be present west of a prominent black buoy in the channel.

At 06:47 Tecumseh opened fire on Ft. Morgan's lighthouse to test her guns. The Confederates held their fire until 07:05 when they began to shoot at the ships in both columns. By this time the Confederate ships had positioned themselves across the mouth of the channel, with Tennessee facing the unprotected side, and they started shooting as well. By 07:30 Tecumseh was about 600 yards away from Tennessee and Craven did not think that he could intercept the Confederate ironclad before Hartford entered the channel unless he passed through the field of "torpedoes", as mines were called at the time, because of his ship's poor maneuverability. He ordered the pilot to steer directly for Tennessee. Ten minutes later, Tecumseh struck a "torpedo" 100 yards from the Tennessee and sank in less than 30 seconds.

TheTecumseh's Survivors

A tiny white comber of froth curled around her bow, a tremendous shock ran through our ship as though we had struck a rock, and as rapidly as these words flow from my pen the Tecumseh reeled a little to starboard, her bows settled beneath the surface, and while we looked her stern lifted high in the air with the propeller still revolving, and the ship pitched out of sight like an arrow twanged from the bow. We were steaming slowly ahead when this tragedy occurred and, being close aboard of the ill-fated craft, we were in imminent danger of running foul of her as she sank. "Back hard" was the order shouted below to the engine room, and, as the Manhattan felt the effects of the reversed propeller, the bubbling water round our bows, and the huge swirls on either hand, told us that we were passing directly over the struggling wretches fighting with death in the Tecumseh.

The effect on our men was in some cases terrible. One of the firemen was crazed by the incident. But the battle was not yet over. After coming to a standstill for a few minutes, during which the commotion of the water set up by the foundered ship passed away, the Manhattan steamed ahead into line and took the duty by now being performed by her lost consort. As the Tecumseh sank to the bottom, the crew of the Hartford sprang to her starboard rail and gave three ringing cheers in defiance of the enemy and in honor of the dying

Perhaps some drowning wretch on the Tecumseh took that cheer in his ears as he sank to a hero’s grave, and we may imagine the sound as it pierced the roar of battle, giving courage to some fainting heart as his face turned for the last time to the light of that sun whose rising and setting was at an end for him..."

Out of a known crew of 110 that sailed that sweltering hot August morning into eternity, only 23 managed to survive her sinking, those being the ones who were stationed either in the turret or the magazine directly below.

Seaman James C. Owston, Landsman Peter McGinnis, Ordinary Seaman John Loughrey and an enlisted man only identified in Farragut's report as "? Farrell" swam to the beach. There they where taken prisoner by the confederates at Fort Morgan and later sent to Andersonville Prison from Mobile on 21 September 1864.

Acting Masters Gardner Cottrell and Charles Langley along with Gunner's Mate Samuel Shinn, Landsman Peter Parker, Quarter Gunner John Gould, Seaman Frank Cousins and Ordinary Seaman Richard T. Collins managed to escape aboard one of the Tecumseh's cutters. Per Cottrell and Langley's report to SECNAV Welles and a letter Parker sent to the New York Times in 1887 to correct an error in a story, they went aboard the tug Buckthorn and later sent to the Tennessee after she surrendered.

Her pilot, John Collins, was in the pilothouse with CDR Tunis Craven. With time for only one man to escape through the scuttle and water rapidly rushing in around them, in an act of self-sacrifice that was venerated in the Navy for decades afterwards, Craven stepped back and allowed Collins to escape first with a simple "after you, pilot." Collins barely made it out before the Tecumseh sank beneath the waves, taking Craven with her.

In an action that would result in the enlisted men under his command being awarded the Medal of Honor, Acting Ensign Henry Clay Nields of the U.S.S. Metacomet took charge of a cutter to rescue the remaining Tecumseh survivors in the water. Those being pilot John Collins, Ordinary Seaman James Burns, Signal Quartermaster Chauncey P. Dean, Landsman Wilkins Tedder, Ordinary Seaman James Lands, Seaman George Major, Seaman James McDonald, Ordinary Seaman Charles Packard, Quartermaster William Roberts, Seaman James Thorn, Coal Heaver William West and Acting Ensign John J. P. Zettick.

After the Sinking

"...The "Tecumseh" is buoyed and lies very near Fort Morgan, say two or three hundred yards from the wharf in a south west-direction, the pilots say in seven fathoms of water with three fathoms over her. We have not been able to ascertain her position not being able to discover her turret.

Despite a sea story that went around in the late 19th century about the entire Tecumseh crew being found dead at their posts by divers a week after the sinking with her CHENG being found reading a letter from his new wife/girlfriend/etc (see "the engineer and the love letter"), the Tecumseh was never dived to recover material or remains unlike other federal vessels that were sunk in and around Mobile Bay in 1864/65.

In August 1873, James E. Slaughter of Mobile and his company, the Bell Boat Wrecking Company, was sold the Tecumseh by then Secretary Robenson for $50. When word spread that Slaughter planned to dynamite the Tecumseh with her crew still entombed to recover the iron used to build her, a battle broke out both in the courts and the halls of Congress.

The United States Attorney for the Southern District of Alabama, George Duskin, filed for and was granted a temporary injunction against the Bell Boat Wrecking Company. The company tried to appeal to Supreme Court, but it appears the case was declined to be heard.

In 1876, a joint resolution in Congress ordered that Slaughter's money be returned with interest and for the Secretary of the Navy to assume the protection of the wreck.

In October of 1877, the New York Sun reported that an unnamed Tecumseh survivor who lived in the city received a letter from Duskin informing him of the granting of a perpetual injunction against anyone interfering with the wreck.

Judging by a letter written by a Carpenter's Mate in 1888 to his hometown newspaper, Ft Morgan was a port of call for the Navy with the sailor mentioning the Tecumseh was discernible on the bottom during calm days. Mobile Bay before the oyster reefs was destroyed during last century was evidently much clearer than it is today.

In 1967, the Tecumseh was found a couple feet under the mud. The Smithsonian dived her, recovered a few artifacts that can be seen in the Hampton Roads Naval Museum (wardroom china and her engineroom gong) and made plans to raise her as a centerpiece for a proposed museum. But money ran out and their plans never came to fruition.

The Tecumseh Buoy

"...Craven, in steering to attack the Tennessee, crossed the torpedo line, and striking one, it exploded under the turret of the Tecumseh, which went down stern first almost in an instance, carrying him down with her. But his death was characterized by an incident which should never be forgotten as long as the English language contains the word chivalry and heroism. It is related by the pilot, Mr. Collins, whose life was saved.

At the moment of the explosion, Craven and the pilot were in the iron tower or pilot house, directly over the turret. There was no way of escape from their iron prison except through a narrow scuttle or opening just sufficient for one to pass through. Seeing the inevitable fate of the vessel, they both instinctively made for this narrow opening. As it is told, when they reached the place together, Craven drew back, in a characteristic way saying, "After you, pilot." Collins who fortunately escape to tell of the act of heroism, says: "There was nothing after me; as I got out the vessel seemed to drop from under me."

It is related of Sir Phillip Sidney, three hundred years ago, that when being carried wounded and bleeding from the battlefield of Zutphen he complained grievously of thirst. A bottle of water was procured for him. As he put it to his mouth, his eye caught the wistful gaze of a mortally wounded soldier eagerly watching his every movement. Taking it untasted from his lips he sent it to the dying man with the words, "Thy necessity is yet greater than mine." He was buried in old St. Paul's among the noble and great of England. Although centuries have rolled away, his country forgets him not, and history still repeating "Thy necessity is yet greater than mine" with the incident, ever keeps the name of Sidney the synonym of true nobility of character and of heroic self-denial.

Noble and chivalric as it was his but a temporarily relinquishment of relief from suffering. Craven's "After you, pilot," cost him his life, the American Navy one of its bravest and most accomplished officers, mankind a hero. No grand old cathedral treasures his remains; no sculptured marble records his heroism; he rests in his iron-turreted tomb off Fort Morgan, with naught but the buoy which swings to and fro with the ebb and flood of the tide in Mobile Bay to mark the scene of his bravery and death..."

Tecumseh buoy off Ft Morgan

Tecumseh buoy off Ft MorganIn stark contrast to the grand memorials at Pearl Harbor; the Tecumseh and her crew whose loss resulted in the Brooklyn heaving to out of fear of striking a mine next and causing RADM Farragut to give his alleged legendary order "damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead", has been marked by nothing more than a succession of nondescript buoys since the first one was placed over the site by order of Farragut in September 1864. Despite the blandness of a buoy, the 19th century Navy appeared to have treated it as their equivalent to the Arizona Memorial.

To see the buoy, enter Fort Morgan and park there. Current access fees are on the the Fort's website (if you are active duty, Ft Morgan is a member of the Blue Star Museums and you can get in free during the summer with your CAC). You can access the beach via the trail at the old wharf near the parking lot inside the fort's property. Once on the beach, walk south towards the entrance of the bay. The yellow cautionary buoy is the closest one near shore just south of the old wharf and can be seen still swinging to and fro with the tide a century and a half later in silent vigil to CDR Craven and eighty-eight of his crew entombed below.

Remains of the old wharf at Ft. Morgan. Tecumseh's buoy is to the right of the center vessel.

Remains of the old wharf at Ft. Morgan. Tecumseh's buoy is to the right of the center vessel. "...Is it not a matter of historical fact that the most precious heritages of the naval and military services have been left in the words uttered by men at the moment of supreme courage in encounters that were not victorious? We have the message left by Lawrence, "Don't give up the ship"; and we have an equally inspiring one from Commander Tunis Augustus Macdonough Craven. The Confederate ram Tennessee was on the port beam of the Tecumseh, inside of the line of torpedoes, and Craven, in his eagerness to engage the ram, passed to the west of the buoy, when suddenly the monitor reeled and sank with almost everyone on board, destroyed by a torpedo. As the Tecumseh was going down Commander Craven and his pilot, John Collins, met at the foot of the ladder leading to the top of turret. Craven, knowing it was through no fault of the pilot but by his own command that the fatal change in her course had been made, stepped back, saying "After you, Pilot." There was no "after" for him. When the pilot reached the top round the vessel seemed to "drop from under," and no one followed. A buoy, that swings to and fro with the ebb and flow of the tide, marks the scene of Commander Craven's bravery and of his death, and beneath, only a few fathoms deep, lies the Tecumseh.

An American naval officer was on board ship with an intelligent Canadian, much interested in American affairs. The two met frequently at ladders and doorways, and on many such occasions the American officer said to his guest, "After you, Pilot." By and by the Canadian said, "What does that mean?" and he was then told the above story of Commander Craven, to which he replied that "the phrase, 'after you, Pilot,' should be the motto of the American Navy, and, in my opinion, it is the most chivalric story I have ever heard..."